When it comes to standardized tests, most people are blinded by science.

Or at least the appearance of science.

Because there is little about these assessments that is scientific, factual or unbiased.

And that has real world implications when it comes to education policy.

First of all, the federal government requires that all public school children take these assessments in 3-8th grade and once in high school. Second, many states require teachers be evaluated by their students’ test scores.

Why?

It seems to come down to three main reasons:

1) Comparability

2) Accountability

3) Objectivity

COMPARABILITY

First, there is a strong desire to compare students and student groups, one with the other.

We look at learning like athletics. Who has shown the most success, and thereby is better than everyone else?

This is true for students in a single class, students in a single grade, an entire building, a district, a state, and between nations, themselves.

If we keep questions and grading methods the same for every student, there is an assumption that we can demonstrate which group is best and worst.

ACCOUNTABILITY

Second, we want to ensure all students are receiving the best education. So if testing can show academic success through its comparability, it can also be used as a tool to hold schools and teachers accountable. We can simply look at the scores and determine where academic deficiencies exist, diagnose them based on which questions students get incorrect and then focus there to fix the problem. And if schools and teachers can’t or won’t do that, it is their fault. Thus, the high stakes in high stakes testing.

Obviously there are other more direct ways to determine these facts. Historically, before standardized testing became the centerpiece of education policy, we’d look at resource allocation to determine this. Are we providing each student with what they need to learn? Do they have sound facilities, wide curriculum, tutoring, proper nutrition, etc.? Are teachers abiding by best practices in their lessons? Many would argue this was a better way of ensuring accountability, but if standardized assessments produce valid results, they are at least one possible way to ensure our responsibilities to students are being met.

OBJECTIVITY

Third, and most importantly, there is the assumption that of all the ways to measure learning, only standardized testing produces objective results. Classroom grades, student writing, even high school graduation rates are considered subjective and thereby inferior.

Questions and grading methods are identical for every student, and a score on the test is proof that a student is either good or bad at a certain subject. Moreover, we can use that score to keep the entire education system on track and ensure it is functioning correctly.

So this third reason for standardized testing is really the bedrock rationale. If testing is not objective, it doesn’t matter if it’s comparable or useful for accountability.

After all, we could hold kids accountable for the length of their hair, but if that isn’t an objective measure of what they’ve learned, we’re merely mandating obedience not learning.

The same goes for comparability. We could compare all students academic success by their ability to come up with extemporaneous rhymes. But as impressive as it is, skill at spitting out sick rhymes and matching them to dope beats isn’t an objective measure of math or reading.

Yet in a different culture, in a different time or place, we might pretend that it was. Imagine how test scores would change and which racial and socioeconomic groups would be privileged and which would suffer. It might – in effect – upend the current trend that prizes richer, whiter students and undervalues the poor and minorities.

So let’s begin with objectivity.

ARE STANDARDIZED TESTS OBJECTIVE?

There is nothing objective about standardized test scores.

Objective means something not influenced by personal feelings or opinions. It is a fact – a provable proposition about the world.

An objective test would be drawing someone’s blood and looking for levels of nutrients like iron and B vitamins.

These nutrients are either there or not.

A standardized test is not like that at all. It tries to take a series of skills in a given subject like reading and reduce them to multiple choice questions.

Think about how artificial standardized tests are: they’re timed, you can’t talk to others, the questions you’re allowed to ask are limited as is the use of references or learning devices, you can’t even get out of your seat and move around the room. This is nothing like the real world – unless perhaps you’re in prison.

Moreover, this is also true of the questions, themselves.

If you’re asking something simple like the addition or subtraction of two numbers or for readers to pick out the color of a character’s shirt in a passage, you’re probably okay.

However, the more advanced and complex the skill being assessed, the more it has to be dumbed down so that it will be able to be answered with A, B, C or D.

The answer does not avoid human influences or feelings. Instead it assesses how well the test taker’s influences and feelings line up with those of the test maker.

If I ask you why Hamlet was so upset by the death of his father, there is no one right answer. It could be because his father was murdered, because his uncle usurped his father’s position, because he was experiencing an Oedipus complex, etc. But the test maker will pick one answer and expect test takers to pick the same one.

If they aren’t thinking like the test maker, they are wrong. If they are, they are right.

MISUNDERSTANDINGS

Yet we pretend this is scientific – in fact, that it’s the ONLY scientific way to measure student learning.

And the reason we make this leap is a misunderstanding.

We misconstrue our first reason for testing with our third. What we take for objectivity is actually just consistency again.

Since we give the same tests to every student in a given state, they show the same things about all students.

Unfortunately, that isn’t learning. It’s likemindedness. It’s the ability to conform to one particular way of thinking about things.

This is one of the main reason the poor and minorities often don’t score as highly on these assessments as middle class and wealthy white students. These groups have different frames of reference.

The test makers generally come from the same socioeconomic group as the highest test takers do. So it’s no wonder that children from that group tend to think in similar ways to adults in that group.

This isn’t because of any deficiency in the poor or minorities. It’s a difference in what they’re exposed to, how they’re enculturated, what examples they’re given, etc.

And it is entirely unfair to judge these children based on these factors.

UNDERESTIMATING HUMAN PSYCHOLOGY

The theory of standardized testing is based on a series of faulty premises about human psychology that have been repeatedly discredited.

First, they were developed by eugenicists like Lewis Terman who explicitly was trying to justify a racial hierarchy. I’ve written in detail about how in the 1920s and 30s these pseudoscientists tried to rationalize the idea that white Europeans were genetically superior to other races based on test scores.

Second, even if we put blatant racism to one side, the theory is built on a flawed and outmoded conception of the human mind – Behaviorism. One of the pioneers of the practice was Edward Thorndike, who used experiments on rats going through mazes as the foundation of standardized testing.

This is all good for Mickey and Minnie Mouse, but human beings are much more complicated than that.

The idea goes like this – all learning is a combination of stimulus and response. Teaching and learning follow an input-output model where the student acquires information through practice and repetition.

This was innovative stuff when B. F. Skinner was writing in the 20th Century. But we live in the 21st.

We now know that there are various complex factors that come into play during learning – bio-psychological, developmental and neural processes. When these are aligned to undergo pattern recognition and information processing, people learn. When they aren’t, people don’t learn.

However, these factors are much too complicated to be captured in a standardized assessment.

As Noam Chomsky wrote in his classic article “A Review of B. F. Skinner’s Verbal Behavior,” this theory fails to recognize much needed variables in development, intellectual adeptness, motivation, and skill application. It is impossible to make human behavior entirely predictable due to its inherent cognitive complexity.

IMPLICATIONS

So we’re left with the continued use of widespread standardized testing attached to high stakes for students, schools and teachers.

And none of it has a sound rational basis.

It is far from objective. It is merely consistent. Therefore it is useless for accountability purposes as well.

Since children from different socioeconomic groups have such varying experiences, it is unfair.

Demanding everyone to meet the same measure is unjust if everyone isn’t given the same resources and advantages from the start. And that’s before we even recognize that what it consistently shows isn’t learning.

The assumption that other measures of academic success are inferior has obscured these truths. While quantifications like classroom grades are not objective either, they are better assessments than standardized tests and produce more valid results.

Given the complexity of the human mind, it takes something just as complex to understand it. Far from disparaging educators’ judgement of student performance, we should be encouraging it.

It is the student-teacher relationship which is the most scientific. Educators are embedded with their subjects, observe attempts at learning and can then use empirical data to increase academic success on a student-by-student basis as they go. The fact that these methods will not be identical for all students is not a deficiency. It is the ONLY way to meet the needs of diverse and complex humanity – not standardization.

Thus we see that the continued use of standardized testing is more a religion – an article of faith – than it is a science.

Yet this fact is repeatedly ignored by the media and public policymakers because there has grown up an entire industry around it that makes large profits from the inequality it recreates.

In the USA, it is the profit principle that rules all. We adjust our “science” to fit into our economic fictions just as test makers require students to adjust their answers to the way corporate cronies think.

In a land that truly was brave and free, we’d allow our children freedom of thought and not punish them for cogitating outside the bubbles.

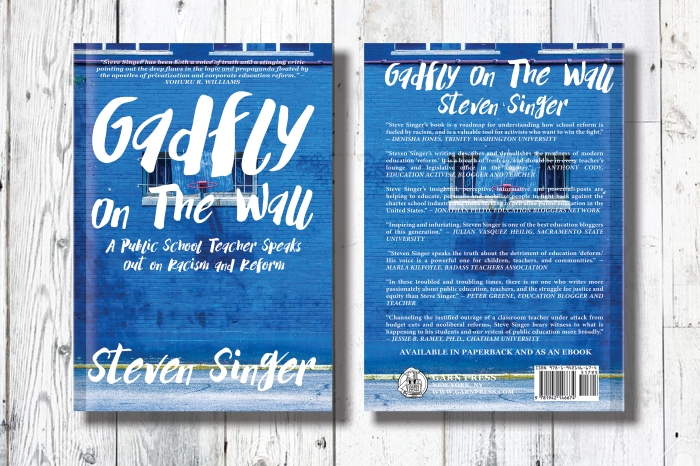

Like this post? I’ve written a book, “Gadfly on the Wall: A Public School Teacher Speaks Out on Racism and Reform,” now available from Garn Press. Ten percent of the proceeds go to the Badass Teachers Association. Check it out!