The most vivid memory I have of my great-grandfather is the tattoo on his arm.

It wasn’t an anchor or a sweetheart’s name or even the old faithful, “Mom.”

It was just a series of digits scrawled across his withered tan flesh like someone had written a note they didn’t want to forget.

Beneath the copious salt and pepper hairs was a stark number, the darkest stain on his skin.

Gramps is a kindly figure in my mind.

He died before I was even 10-years-old. All I really remember about him are wisps of impressions – his constant smile, a whiff of mothballs, how he always seemed to have butterscotch candies.

And that tattoo.

I think it was my father who told me what it meant.

When he was just a young man, Gramps escaped from Auschwitz. A guard took pity on him and smuggled him out.

His big European family didn’t make it.

My scattered relatives in the United States are all that are left of us.

Those are the only details that have come down to me. And Gramps isn’t here to add anything further.

But his tattoo has never left me.

It’s become a pillar of my subconscious.

The fact that someone could look at my kindly Gramps and still see fit to tattoo a numeric signifier on him as if he were an animal.

A little reminder that he wasn’t human, that he shouldn’t be treated like a person, that he was marked for erasure.

If I look at my own arm, there is no tell-tale integer peeking through the skin. But I am keenly aware of its presence.

I know that it’s there in a very real sense.

It is only the American dream that hides it.

Coming to this country, my family has made a deal, something of a Faustian bargain, but it’s one that most of us have accepted as the price of admission.

It’s called whiteness.

I am white.

Or I get to be white. So long as I suppress any differences to the contrary.

I agree to homogenize myself as much as possible and define myself purely by that signifier.

White. American. No hyphen necessary.

Anything else is secondary. I don’t have to deny it, but I have to keep it hidden until the right context comes to bring it out.

During Octoberfest I have license to be German. When at international village I can root for Poland. And on Saturdays I can wear a Kippah and be Jewish.

But in the normal flow of life, don’t draw attention to my differences. Don’t show everyone the number on my arm.

Because America is a great place, but people here – as in many other places – are drawn to those sorts of symbols and will do what they can to stamp them out.

I learned that in school when I was younger.

There weren’t a lot of Jewish kids where I grew up. I remember lots of cracks about “Jewing” people down, fighting against a common assumption that I would be greedy, etc. I remember one girl I had a crush on actually asked to see my horns.

And of course there were the kids who chased me home from the bus stop. The scratched graffiti on my locker: “Yid.”

The message was clear – “You’re different. We’ll put up with you, but don’t ever forget you are NOT one of us.”

There were a lot more black kids. They didn’t get it any easier but at least they could join together.

It seemed I had one choice – assimilate or face it alone.

So I did. I became white.

I played up my similarities, never talked about my differences except to close friends.

And America worked her magic.

So I’ve always been aware that whiteness is the biggest delusion in the world.

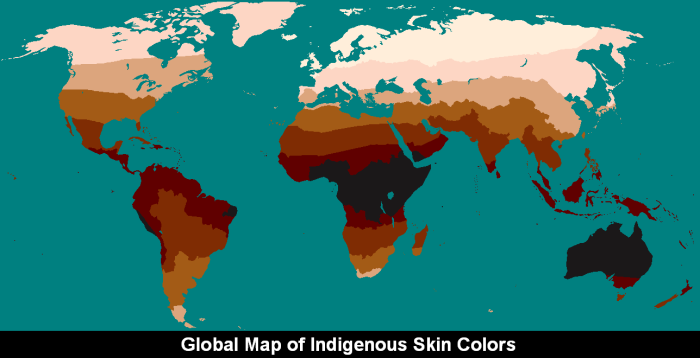

It’s not a result of the color wheel. Look at your skin. You’re not white. You’re peach or pink or salmon or rose or coral or olive or any of a million other shades.

Whiteness has as much to do with color as Red has to do with Communism or Green has to do with environmental protection.

It is the way a lose confederacy of nationalities and ethnicities have banded together to form a fake majority and lord power over all those they’ve excluded.

It’s social protection for wealth – a kind of firewall against the underclass built, manned and protected by those who are also being exploited.

It’s like a circle around the wealthy protecting them from everyone outside its borders. Yet if everyone banded together against the few rich and powerful, we could all have a more equitable share.

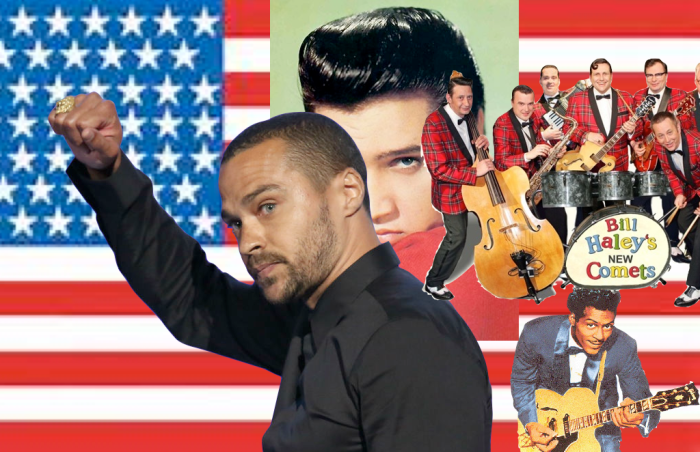

But in America, social class has been weaponized and racialized.

You’ll see some media outlets talking about demographics as if white people were in danger of losing their numerical majority in this country in the next few decades. But there’s no way it’s ever going to happen.

Today’s xenophobia is a direct response to this challenge. Some are trying to deport, displace and murder as many black and brown people as possible to preserve the status quo.

But even if that doesn’t work, whiteness will not become a minority. It will do what it has always done – incorporate some of those whom it had previously excluded to keep its position.

Certain groups of Hispanics and Latinos probably will find themselves allowed to identify as white, thereby solidifying the majority.

Because the only thing that matters is that there are some people who are “white” and the rest who are not.

Long ago, my family experienced this.

Before I was born, we got our provisional white card. And if I want, I can use it to hide behind.

I’ve been doing it most of my life.

Every white person does it.

It’s almost impossible not to do it.

How do you deny being white?

At this point, I could throw back my head and shout to the heavens, “I’M NOT WHITE!” and it wouldn’t matter.

Only in a closed environment like a school or a job or in a social media circle can you retain the stigma of appearing pale but still being other.

In everyday life, it doesn’t matter what you say, only how you appear.

I can’t shout my difference all the time. Every moment I’m quiet, I’ll still be seen as white.

It’s not personal. It’s social. It’s not something that happens among individuals. It’s a way of being seen.

The best I can do is try to use my whiteness as a tool. I can speak out against the illusion. I can stand up when people of color are being victimized. I can vote for leaders who will do something to dismantle white supremacy.

Not because I am some kind of savior, but because I know that my own freedom is tied to the freedom of those being oppressed by a system that provides me certain privileges.

But let me be clear: doing so is not the safe way to go.

In defending others you make yourself a target.

I get threats all the time from racists and Nazis of all sorts. They say they can tell just by looking at me that I’m not white at all.

The worst part is I’m not sure what I am anymore.

I don’t go to synagogue. I don’t even believe in God. But I’m Jewish enough to have been rounded up like Gramps was, so I won’t deny that identity. It’s just that I’m more than one thing.

That’s what whiteness tries to reduce you to – one thing.

I don’t want it anymore.

I’m not saying I don’t like the protection, the ability to be anonymous, the easy out.

But it’s not worth it if it has to come with the creation of an other.

I don’t want to live in a world where people of color are considered less than me and mine.

I don’t want to live in a world where they can be treated unfairly, beaten and brutalized so that I can get some special advantage.

I don’t want to live in a world where human beings are tattooed and numbered and sent to their deaths.

Because the Holocaust is not over.

Neither is Jim Crow or lynching or a thousand other marks of hatred and bigotry.

Nazis march unmasked in our streets. Our prisons are the new plantation. And too many of our police use murder and atrocity to ensure the social order.

As long as we allow ourselves to be white, there will be no justice for both ourselves and others.

So consider this my renunciation of whiteness – and I make it here in public.

I know that no matter what I say, I will still be seen as part of the problem. And I will still reap the rewards.

But I will use what power is given me to tear it down.

I’m burning my white card.

I know it’s a symbolic gesture. But I invite my white brothers and sisters to add theirs to the flames.

Let us make a conflagration, a pillar of fire into the sky.

Let whiteness evaporate as the smoke it is.

Let us revel in the natural hues of our faces as we watch it burn.

Like this post? I’ve written a book, “Gadfly on the Wall: A Public School Teacher Speaks Out on Racism and Reform,” now available from Garn Press. Ten percent of the proceeds go to the Badass Teachers Association. Check it out!

WANT A SIGNED COPY?

Click here to order one directly from me to your door!